On Disruptive Art and Business

English version: Tatiana Bazzichelli, Aarhus, May 2010

In 1981, writing about the concept of ‘ethnographic surrealism’, James Clifford referred to Lautreamont’s definition of beauty: “The chance encounter on a dissecting table of a sewing machine and an umbrella” [1].

James Clifford described the ethnographic attitude as ways of dismantle culture’s hierarchies and holistic truths. Cultural orders are substituted with unusual juxtapositions, decomposition of reality, fragments and unexpected combinations; the objective of research is not really seen in rendering the unfamiliar comprehensible as part of the ethnographic tradition wanted, but in making the familiar strange “by a continuous play of the familiar and the strange, of which ethnography and surrealism are two elements” [2] [3].

Aesthetics that values fragments, and a methodology of revealing evident contradictions without solving them, but rather leaving them open to new interpretations, as a form of cultural criticism and a way to understand contemporary phenomena. This method, showing our present as a collage of incongruities which don’t just resolve in a dialectic of oppositions, give us input to think about future tactical strategies in the field of art and media.

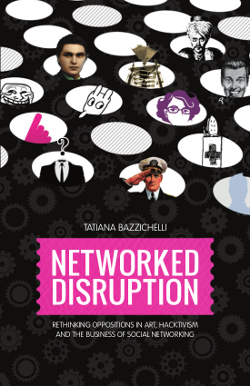

The present essay deals with the concept of social networking and with the development of folksonomies through social media platforms. It reflects on the status of artistic and activist practices in the Web 2.0 analyzing interferences between networking and business. I will start referring to the dialectical perspective ‘Ästhetisierung der Politik – Politisierung der Kunst’ (aesthetization of politics – politicization of art) by Walter Benjamin [4], in the present context used to describe the development of social networks as an aesthetic representation of social commons, and consequently, to analyze possible strategies of artistic and activist interventions in the social media. Another fragment of my analysis shows how the endless cycles of rebellion and transgression coexist with the development of business culture in Western society, breaking the juxtaposition between art as an aesthetic form of collective representation and art as a form of political intervention by a collectivity. I will show how, since the Avant-gardes, critical art and business have had evident signs of interconnection, especially in the frame of the collective representation of the masses. In conclusion, I will develop the concept of The Disruptive Art of Business as a form of artistic intervention within the business field of Web 2.0, where artists and activists, conscious of the pervasive presence of consumer culture in our daily life, react strategically and playfully from within. The essay ends suggesting possible strategies of artistic action, as a result of framing open contradictions without wanting to resolve them through an encompassing synthesis.

The Aesthetics of the Masses

In the Artwork Essay (1936) Walter Benjamin reflects on the advent of photography and cinema in the modern society and connects the emergence of consumer culture to the development of technological reproducibility, analyzing the consequent death of the artwork’s aura. In the age of cinematic media revolution the masses become active players in the transformation of the arts, and the arts, by disregarding the aura through mechanical reproduction, would inherently be based on the practice of politics. Authenticity and value of a unique and singular work of art would be substituted by a new media aesthetics, in which the masses would recognize themselves (Søren Pold, 1999).

In the Artwork Essay (1936) Walter Benjamin reflects on the advent of photography and cinema in the modern society and connects the emergence of consumer culture to the development of technological reproducibility, analyzing the consequent death of the artwork’s aura. In the age of cinematic media revolution the masses become active players in the transformation of the arts, and the arts, by disregarding the aura through mechanical reproduction, would inherently be based on the practice of politics. Authenticity and value of a unique and singular work of art would be substituted by a new media aesthetics, in which the masses would recognize themselves (Søren Pold, 1999).

According to Benjamin, the destruction of the aura took place already in the history of art through the Dadaist works, which “they branded as reproduction with the very means of production” (Walter Benjamin 1936: 238). On the contrary, in the epilogue of the Artwork Essay, Benjamin describes the attempt of Fascism to organize the masses “without affecting the property structure which the masses strive to eliminate”. Therefore, “the logical result of Fascism is the introduction of aesthetics into politics” (Walter Benjamin 1936: 241). The phenomenon of the aesthetics of the masses and the emerging of a new social mentality through collective gatherings in the urban space was very well described in 1927 by Siegfried Kracauer in his Weimar Essays, known as Das Ornament der Masse (published in English as The Mass Ornament) [5].

Benjamin sees the Ästhetisierung der Politik as the evidence of a propagandistic effort that culminates in the aesthetics of war, quoting the Manifesto on the Ethiopian colonial war written by the Futurist Filippo Tommaso Marinetti; Kracauer describes the gatherings in urban spaces and the mechanical movement of line dancers, the mass ornaments, as celebrations of capitalist society, where the single individual is not conscious of being part of a bigger production design. The epilogue of the Artwork Essay might be considered quite apocalyptic, revealing the risks of using mechanical equipment and technological features to perpetuate totalitarian propaganda, but it should be framed in the political situation of the mid-1930s, when Walter Benjamin wrote it. As Søren Pold points out “the Artwork Essay opens up a critical space through its reflection on media, which are neither technologically deterministic […] nor blind to the revolutionary effects of media on the political and cognitive levels, on the basic level of experience” [6].

With the well known dialectical conclusion of the Artwork Essay, Walter Benjamin states: “Mankind, which in Homer’s time was an object of contemplation for the Olympian gods, now is one for itself. Its self-alienation has reached such a degree that it can experience its own destruction as an aesthetic pleasure of the first order. This is the situation of politics which Fascism is rendering aesthetic. Communism responds by politicizing art” (Walter Benjamin 1936: 242). But even if Benjamin criticized the progressive aesthetization of politics, he was never against technological development. He saw in the film industry a tool for mobilizing the masses, and in the consumer culture a territory in which the masses could find new forms of self-expression, as he pointed out in his unfinished project on the nineteenth century, known as Das Passagenwerk or, in English, The Arcades Project. Benjamin shows a polyphonic attitude in understanding modern society, where the demand for a politicization of art is not alien to the experience of Baudelaire’s urban flâneur in the arcades of the metropolis. The flâneur abandons himself in the crowd, and emphatically connects with the goods of mass consumerism, the shiny signs of business, through his “casual eye” and his meditative trance. “In the flâneur, the intelligentsia sets foot in the marketplace” [7].

The Tiller Girls Show. Sunday night at the London Palladium. Photo by Horace Ward (Rolleiflex Camera), London, c.1960

The Aesthetics of Common Participation

After the emergence of Web 2.0 (Tim O’Reilly, 2004) we are facing a progressive commercialization of web-based contexts of sharing and social relationships, which want to appear open and progressive, but which are indeed transforming the meaning of communities and networking, placing it into the boundaries of the marketplace. From the use of technology of cooperation to create self-organized cultural activity, we are today in the domain of “business analysts who seek collaboration as a tool to grow wealth for the already prosperous” [8]. Social networks are a clear example of the emerging trend of incorporating our daily life in a net of constant connectivity, where our exposed subjectivity becomes attractive merchandise, following the process of “mass amateurization” as defined by Lawrence Lessig and Joi Ito. But as Lovink and Scholz argued, in many projects of Web 2.0 social community “there is no total autonomy of collaborative projects”, and “working together does not exempt us from systemic complicity” (Geert Lovink and Trebor Scholz, 2007: 10). They also argue that even if contexts of sharing are becoming more accessible than before thanks to social media, this phenomenon might be a mirror of a lack of desire of common participation. Therefore, it is not surprising to notice that many online independent communities and mailing-lists very active in the netculture and net art between mid-1990s and mid-2000s are today much less participated, while a good portion of their members is quite active in social networks such as Facebook, which however require a less meditative involvement [9].

An interesting example of the shift of networked art as a collective and sharing practice to the economically oriented modalities of interactions in the Web 2.0 is given by the art of crowdsourcing of Aaron Koblin. The artist uses the Amazon Mechanical Turk to create artworks, which result from a combination of tasks, performed by a group of people, gathered through an open call asking for contributions. The contributors are paid a specific amount of money after delivering their work. Koblin used the strategy of crowdsourcing to create works such as Bicycle Built for Two Thousand, Ten Thousand Cents and The Sheep Market [10].

But, like the collective dance compositions of the Tiller Girls described by Siegfried Kracauer, even if these works involved many people who perform a single task, the members of the group are not in connection with each other. They are not conscious of the global design they are going to be part of, and beside the economic revenue of the crowdsourcing, which is usually almost insignificant, the people’s involvement lack in purpose. What is gained at the end of the process is an aesthetic representation of the collectivity, but the collective doesn’t exist per se. However, we should also argue that, it is exactly through Koblin’s representation of the collectivity that we are able to understand it as a whole, and therefore, to investigate its simulacra while performing them. But we can only reach this level of consciousness at the end of the process, when the “mass ornament” is complete. What is lacking in these experiments is the possibility of being active subjects, and even if we finally become aware of the production process, the collectivity is objectified.

If we go back thirty years to the practice of mail art, it involved individuals linked by belonging to a non-formalized network of common interests, which resulted in exchanging self-made postcards, handmade stamps, rubber stamps, envelops and many other creative objects shared though the postal network. In this case, the network was free and open to everyone, not economically oriented, and the artists participated to the call just for fun or for the pleasure of sharing. People were all part of an emotional network of common interests, creating a common thread that was moved by the desire for free cooperation. The mass ornaments of Aaron Koblin instead show a deep aspect of our contemporary media society and of its production’s process: we are all connected monads and we are trapped in simulacra of interaction.

To the aesthetization of networking through business strategies, should we answer with a politicization, or better activist intervention, in the business field through art practice?

Art of Disruption in Networking Business

The Disruptive Art of Business is a concept I created (2010) to describe open possibilities of transformations and interventions adopting disruptive business strategies as a form of art. According to Wikipedia, “disruptive innovation is a term used in business and technology literature to describe innovations that improve a product or service in ways that the market does not expect” [11]. Wikipedia brings the example of ‘new-market disruption’ caused by the GNU/Linux Operating System, which “when introduced was inferior in performance to other server operating systems like Unix and Windows NT”, but by being less expensive “after years of improvements Linux is now installed in 87.8% of the worlds 500 fastest supercomputers” [12]. To apply this concept of disruptive innovation into the art field, and at the same time open up a critical perspective towards business, it is necessary to analyze the marketplace from within, trying to understand how it works and which are its strategies and mechanisms of production. A challenge for artists and activists who want to deal with networking in the configuration it has taken today, and who should become able to see the collective ‘ornamental design’ we are part of from above. At the beginning of the 2000s a motto of activists and hackers was: “Don’t hate the media, become the media”. Today this approach should be applied to business strategies, to tactically respond to the progressive commercialization of contexts of sharing and networking.

Taking inspiration from Benjamin’s description of the flâneur, artists should walk across the shiny passages of consumer culture, acting as shoppers that don’t buy goods, but that experience them through empathy and intimate understanding (Einfühlung), through an astonished glance. The Italian anthropologist Massimo Canevacci, referring to the correspondence between Walter Benjamin and Theodor W. Adorno (dated 1913-1940), points out: “Benjamin realizes that already in the nineteenth century the passages – along with the Great Exhibitions – logically replace the centrality of the social factory, spreading consumption and not productive work. Spreading empathic identification and not alienation” [13]. The experience of the astonished facticity, a concept first proposed by Adorno and then interpreted by Benjamin as “a fragmented and mobile constellation of objects-things-commodities” (Massimo Canevacci, 2007), becomes fundamental to critically understand the development of the modern society with a perspective from the inside [14].

To perform the concept of Disruptive Art of Business, artists and activists should create an intimate relation with their subject of criticism, to be able to become aware of it, and at the same time, to create disruptive innovation. While disrupting the machine, and performing criticism, it might be possible to accomplish a new critical prospective, by staging an attitude which we might consider “a participant observation among the artifacts of a defamiliarized cultural reality” (James Clifford, 1991: 542). The challenge is once again to make the familiar strange, as we wrote above describing the ethnographic surrealism’s approach.

Some artists and activists in the past few years had already moved towards this direction, even if an encompassing criticism about business strategy through artistic practices has still to be formulated, and deeply performed. However some artworks, which deal with Web 2.0, contributed to open space for business criticism subverting its strategies from within. The Google AdWords Happening (2001) by Christophe Bruno; GWEI, Google Will Eat Itself (2005), and Amazon Noir (2006), by UBERMORGEN.COM, Paolo Cirio and Alessandro Ludovico; Seppukoo (2009) by Les Liens Invisibles; Web 2.0 Suicide Machine (2009) by Moddr.net, made possible to acknowledge how business works, introducing unexpected incongruities in the capitalist structure and provoking unusual feedback while performing the machine [16].

In order to move forward we need to ask ourselves whether it make sense today to speak about “counterculture”, when cooperation, sharing and networking has become the motto of the Web 2.0 business. The act of responding with a radical opposition does not look like an effective practice anymore. We are already involved in the “capitalist ornament” since long [15]. But instead of just being trapped inside it, disappearing in the crowd and ending up in the collective noise, the challenge is to become aware of its mechanism.

The act of performing capitalism, keeping the dialectic open, becomes a critical statement.

Notes:

[1] Ducasse, I., Oeuvres Completes De Lautreamont. Les Chants De Maldoror. Poesies. Lettres. Paris: Garnier-Flammarion, 1969, p. 234.[2] Clifford, J., 1981, “On Ethnographic Surrealism”, in Comparative Studies in Society and History, Vol. 23, No. 4 (Oct, 1981), pp. 542, Cambridge University Press.

[3] The concept of defamiliarization was first coined in 1917 by Viktor Shklovsky in his essay “Art as Technique” referring to the process of aesthetic perception as “estrangement”, in which art objects, while experienced, are made unfamiliar. To investigate further the matter of interpretation of cultures and describing the self in both its individual and collective projections, see the essay by Vincent Crapanzano: “Hermes’ Dilemma: The Masking of Subversion in Ethnographic Description” in Clifford J., and Marcus G. E., 1986, Writing Culture. The Poetics and Politics of Ethnography, Berkeley, University of California Press. Thanks respectively to Geoff Cox and Luca Simeone to pointing out these references.

[4] Benjamin W., 1936, Das Kunstwerk im Zeitalter Seiner Technischen Reproduzierbarkeit, Eng. eds., 1968, “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction”, in Illuminations. Essay and Reflections, New York, Schocken Books.

[5] Kracauer, S., 1927, Das Ornament der Masse, Eng. eds., 1995, The Mass Ornament. Weimar Essays, Cambridge, Harvard University Press.

[6] Pold, S., 1991, “An Aesthetic Criticism of the Media: The Configuration of Art, Media and Politics in Walter Benjamin’s Materialistic Aesthetics”, in Parallax, Vol. 5, No. 3, Routledge, UK, pp. 23.

[7] Benjamin, W., 1935, Paris, Hauptstadt des XIX Jahrhunderts (Exposé of the Arcades Projects), Eng. eds., 2008, “Paris, The Capital of the Ninetheen Century”, in Benjamin., W., The Work of Art in the Age of Its Technological Reproducibility and Other Writings on Media, Cambridge, Harvard University Press.

[8] Lovink, G., Scholz, T., (edited by), 2007, “Collaboration on the Fence”, in The Art of Free Cooperation, New York, Autonomedia, pp. 9.

[9] For more information on this topic, follow the thread “Has Facebook superseded Nettime?” started by Florian Cramer on 21 September 2009 on the Nettime mailing-list: www.nettime.org/Lists-Archives/nettime-l-0909/msg00024.html. My answer to the matter was published on the Nettime Digest (September 25), and, later, on my blog: www.networkingart.eu/2009/10/has-facebook-superseded-nettime.

[10] Respectively: www.bicyclebuiltfortwothousand.com, www.tenthousandcents.com, www.thesheepmarket.com. See the notes below the pictures for more information.

[11] Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Disruptive_technology.

[12] Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, Ibidem.

[13] Canevacci, M., 2003, “Una stupita fatticità. Verso un’etnografia della reificazione”, in Avatar. Dislocazioni tra antropologia e comunicazione, No. 4, October 2003, Rome, Meltemi, pp. 36. The above English translation is by Tatiana Bazzichelli.

[14] Canevacci Ribeiro, M., 2007, Una stupita fatticità. Feticismi visuali tra corpi e metropoli, Milan, Costa & Nolan. English abstract by Canevacci Ribeiro, M., An Astonished Facticity. Ethnography on Visual Fetishisms, online at: www.simon-yotsuya.net/profil/fatticita.htm.

[15] The Google AdWords Happening by Christophe Bruno (www.iterature.com/adwords) consists in a poetry advertisement campaign on Google AdWords, where ads become provocative poems referring to specific keywords searched by users and previously bought by the artist to generate revenue. Google Will Eat Itself (http://gwei.org) by UBERMORGEN.COM, Paolo Cirio and Alessandro Ludovico is based on the automatic generation of Adsense revenues, used to purchase Google stocks to provoke an auto-cannibalistic business process; Amazon Noir (www.amazon-noir.com), instead, discovers the bugs in the “Search Inside the Book” Amazon’s function and makes copyright protected books ready for free download. Last but not least, Seppukoo (www.seppukoo.com) by Les Liens Invisibles and Web 2.0 Suicide Machine (http://moddr.net/category/projects) by Moddr.net stress the limits of social networking simulating users’ virtual suicides to conquer again their own – exploited – identity. Thanks to Søren Pold for pointing out Christophe Bruno’s activity and for advising on the matter.

[16] As described on the book: Frank T., 1997, The Conquest of Cool. Business Culture, Counterculture, and the Rise of Hip Consumerism, Chicago University Press. See also: Turner F., 2007, From Counterculture to Cyberculture. Stewart Brand, the Whole Earth Network, and the Rise of Digital Utopianism, Chicago University Press.

Bibliography:

Benjamin W., 1935-39, Charles Baudelaire. Ein Lyriker im Zeitalter des Hochkapitalismus, Suhrkamp Verlag, 1955. Eng. eds., 1973, A lyric Poet in the Era of High Capitalism, New Left Review Editions, London.

Benjamin W., 1936, Das Kunstwerk im Zeitalter Seiner Technischen Reproduzierbarkeit, Eng. eds., 1968, “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction”, in Illuminations. Essay and Reflections, New York, Schocken Books.

Benjamin, W., 1935, Paris, Hauptstadt des XIX Jahrhunderts (Exposé of the Arcades Projects), Eng. eds., 2008, “Paris, The Capital of the Ninetheen Century”, in Benjamin., W., The Work of Art in the Age of Its Technological Reproducibility and Other Writings on Media, Cambridge, Harvard University Press.

Canevacci Ribeiro, M., 2007, Una stupita fatticità. Feticismi visuali tra corpi e metropoli, Milan, Costa & Nolan.

Canevacci, M., 2003, “Una stupita fatticità. Verso un’etnografia della reificazione”, in Avatar. Dislocazioni tra antropologia e comunicazione, No. 4, October 2003, Rome, Meltemi.

Clifford, J., and Marcus, G. E., 1986, Writing Culture. The Poetics and Politics of Ethnography, Berkeley, University of California Press.

Clifford, J., 1981, “On Ethnographic Surrealism”, in Comparative Studies in Society and History, Vol. 23, No. 4 (Oct, 1981), pp. 542, Cambridge University Press.

Crapanzano, V., 1986 “Hermes’ Dilemma: The Masking of Subversion in Ethnographic Description” in Clifford J., and Marcus G. E., 1986, Writing Culture. The Poetics and Politics of Ethnography, Berkeley, University of California Press.

Ducasse, Isidore. Oeuvres Completes De Lautreamont. Les Chants De Maldoror. Poesies. Lettres. Paris: Garnier-Flammarion, 1969.

Frank T., 1997, The Conquest of Cool. Business Culture, Counterculture, and the Rise of Hip Consumerism, Chicago University Press.

Kracauer, S., 1927, Das Ornament der Masse, Eng. eds., 1995, The Mass Ornament. Weimar Essays, Cambridge, Harvard University Press.

Lovink, G., Scholz, T., (edited by), 2007, The Art of Free Cooperation, New York, Autonomedia.

Pold, S., 1991, “An Aesthetic Criticism of the Media: The Configuration of Art, Media and Politics in Walter Benjamin’s Materialistic Aesthetics”, in Parallax, Vol. 5, No. 3, Routledge, UK.

Shklovsky, V., 1917, “Art as Technique” in Lemon L. T., and Reis, M., Eds., Russian Formalist Criticism, University of Nebraska Press, 1965.

Turner F., 2007, From Counterculture to Cyberculture. Stewart Brand, the Whole Earth Network, and the Rise of Digital Utopianism, Chicago University Press.

Turner, F., “Burning Man at Google: A Cultural Infrastructure for New Media Production”, New Media & Society, Vol.11, No.1-2 (April, 2009), 145-66.

Category: Bazzichelli PhD Research, Disruptive Business

Tagged: Bazzichelli, Disruptive Business, Siegfried Kracauer, Social media, Social networking, Walter Benjamin, Web 2.0

Tatiana Bazzichelli – Networking Art

Tatiana Bazzichelli – Networking Art